Festival de Locarno: «Ventos de agosto» de Gabriel Mascaro (español/inglés)

Siguiendo con la costumbre de tener críticos, cineastas y amigos invitados a escribir críticas en festivales en los que no podemos estar presentes (el año pasado el realizador chileno Alejandro Fernández Almendras aportó una notable reflexión sobre la película de Albert Serra) , en esta edición Micropsia contará con los invalorables aportes de la crítica […]

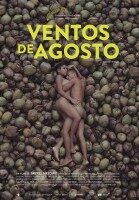

Siguiendo con la costumbre de tener críticos, cineastas y amigos invitados a escribir críticas en festivales en los que no podemos estar presentes (el año pasado el realizador chileno Alejandro Fernández Almendras aportó una notable reflexión sobre la película de Albert Serra) , en esta edición Micropsia contará con los invalorables aportes de la crítica austríaca Alexandra Zawia, que aquí arranca su selectiva cobertura de Locarno con una notable crítica de la película brasileña VIENTOS DE AGOSTO, de Gabriel Mascaro. Aquí, en versión traducida (por mí, se aceptan correcciones) y abajo, en el inglés original.

Siguiendo con la costumbre de tener críticos, cineastas y amigos invitados a escribir críticas en festivales en los que no podemos estar presentes (el año pasado el realizador chileno Alejandro Fernández Almendras aportó una notable reflexión sobre la película de Albert Serra) , en esta edición Micropsia contará con los invalorables aportes de la crítica austríaca Alexandra Zawia, que aquí arranca su selectiva cobertura de Locarno con una notable crítica de la película brasileña VIENTOS DE AGOSTO, de Gabriel Mascaro. Aquí, en versión traducida (por mí, se aceptan correcciones) y abajo, en el inglés original.

Alexanda Zawia

««La falta de significado de la vida fuerza al hombre a crear su propio significado. Y si ese sentido puede ser escrito o pensado, también puede ser filmado» (Stanley Kubrick)

El hotel en el que estoy está frente a un cementerio. Se extiende bastante generosamente por debajo de palmeras y pinos, rodeado de paredes de piedra que lucen muy antiguas. Frente a su entrada principal hay un bello y alto panteón dominando el escenario, impresionando como un recordatorio para todos aquellos que se mueven más rápido que la muerte.

Entrar al panteón es como atravesar una puerta que nos saca del calor irritante y de la incesante corriente de ruidos y luces diurnas para introducirnos en una zona de sombras, un pozo vacío y tranquilo que está como fuera del tiempo. El panteón ofrece protección, huele a humedad, moho y la clase de confort que se otorga al final de una batalla perdida. Por fuera, las paredes son cálidas, imperturbables y tocarlas me hace recordar a una línea de diálogo de VIENTOS DE AGOSTO, de Gabriel Mascaro: “Las piedras respiran. Tienen pulmones, como cualquier ser humano”.

Puede parecer raro, al principio, lo que Jeison (Geová Manoel Dos Santos) le está tratando de explicar a un científico que se ha llegado hasta ahí a grabar los vientos, el aire, los ruidos: un arqueólogo del futuro, en realidad. Ambos miran a una pileta de piedras naturales en la cual el agua está comprimida dentro del movimiento de las olas, subiendo y bajando, subiendo y bajando: son las piedras las que hacen respirar al mar.

Puede parecer raro, al principio, lo que Jeison (Geová Manoel Dos Santos) le está tratando de explicar a un científico que se ha llegado hasta ahí a grabar los vientos, el aire, los ruidos: un arqueólogo del futuro, en realidad. Ambos miran a una pileta de piedras naturales en la cual el agua está comprimida dentro del movimiento de las olas, subiendo y bajando, subiendo y bajando: son las piedras las que hacen respirar al mar.

El debut de ficción de Mascaro es una película llena de bellas imágenes y momentos como éste, y su poder está en el hecho de que logra capturarlos de manera modesta, casi casualmente, dando a sus atentas observaciones de la naturaleza y de sus alrededores todo el espacio que necesitan y justo el espacio que pueden llenar.

Claramente, es un director que posee un fino sentido del juego que existe entre los mundos interiores y las condiciones exteriores, algo que mostraba también en su anterior documental, DOMESTICAS, sobre mucamas en el Brasil actual, filme que también hablaba de la imposibilidad del país de lidiar y revivir una historia de esclavitud.

Para VIENTOS…, Mascaro transformó un área al lado de la costa de Pernambuco, en el noreste de Brasil alrededor de la Zona de Convergencia Intertropical, la que produce los llamados vientos de agosto, famosos por sus distintivos sonidos.

Poca gente vive en el pequeño y aparentemente alejado asentamiento donde Mascaro ubica a Jeison y a su novia Shirley (Dandara de Morais), quienes parecen los remotos equivalentes de unos jóvenes e inocentes Adán y Eva. Pasan sus días en un pequeño bote, tomando sol y lanzándose al mar, recolectando cocos y haciendo secretamente el amor sobre una pila de frutas verdes cuando van en camino a descargar su camión.

Poca gente vive en el pequeño y aparentemente alejado asentamiento donde Mascaro ubica a Jeison y a su novia Shirley (Dandara de Morais), quienes parecen los remotos equivalentes de unos jóvenes e inocentes Adán y Eva. Pasan sus días en un pequeño bote, tomando sol y lanzándose al mar, recolectando cocos y haciendo secretamente el amor sobre una pila de frutas verdes cuando van en camino a descargar su camión.

Hay un fotógrafo circulando alrededor del lugar, tratando de vender sus retratos a gente que no quiere gastar su poco dinero en recomprar sus recuerdos de manos de un extraño. Y, en un momento, vemos un bote con turistas pasando discretamente por un costado del cuadro.

La madre de Shirley le ha asignado hacerse cargo de su frágil abuela y Jeison queda como el único apoyo de su también enfermo padre. Pero a diferencia de él, ella se siente atrapada en su nueva tarea y trata de aprender a convertirse en una artista del tatuaje. Para empezar, deja muestras de su creatividad en el rapado trasero de un evidentemente molesto cerdito.

Sin embargo, un día en el que las cosas parecen seguir estando igual, Jaison cambia. Encuentra una calavera mientras bucea, lo que causa un quiebre creciente en la burbuja un tanto naive y protegida en la que Shirley y él parecían seguir viviendo. Irritados por esta sorprendente aparición de la nada, Shirley y Jason tratan de descubrir a quien perteneció esa calavera (su único dato es un diente de oro todavía pegado al hueso). Mascaro hábilmente aprovecha esta oportunidad para mantener un diálogo divertido y de bajo perfil que sirve como introducción a un sutil discurso que el filme desarrollará de ahí en adelante.

Como un cauto presagio, esa calavera difícilmente había preparado a Jeison para el descubrimiento de un cuerpo muerto flotando en el mar un par de días después. Al sacarlo del agua, Jeison se enfrenta a la mortalidad entrando de lleno en su vida de una manera que, al principio, no sabe cómo manejar.

Como un cauto presagio, esa calavera difícilmente había preparado a Jeison para el descubrimiento de un cuerpo muerto flotando en el mar un par de días después. Al sacarlo del agua, Jeison se enfrenta a la mortalidad entrando de lleno en su vida de una manera que, al principio, no sabe cómo manejar.

De una manera siempre sutilmente juguetona y con un sentido del humor permanente, además de un excelente uso del sonido diegético, Mascaro –que también hizo las veces de director de fotografía aquí– encuadra a los personajes en planos espaciosos en los cuales les permite moverse. Y al mismo tiempo, logra dar cuenta de la poderosa magnitud de la naturaleza y del inevitable transcurso del tiempo, revelando como las personas están sujetas a esas fuerzas, sin jamás traicionar su dignidad.

Jeison, a diferencia de Shirley, solo gradualmente reconoce una sensación interna de protesta. Ha sido feliz viviendo al ritmo de la naturaleza que lo rodea, respirando como una piedra, quieto y sin investigar demasiado las cosas. Es solo ahora cuando empieza a darse cuenta que tampoco él permanecerá ahí para siempre. Ni ahí ni en ningún otro lado, no en este mundo. Está en el proceso de comprender los límites de la vida, pero todavía no puede aceptar esa cualidad transitoria de la existencia. Teme que el mar vaya a llevarse todo en algún punto y en su intento de prevenir eso, coloca una piedra en medio del cementerio del pueblo, que está en la playa. Por supuesto, los ataúdes serán arrastrados por el mar y fuera de la arena tarde o temprano, pero mientras estén ahí puedo mirar las firmes bóvedas una vez más y luego partir.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

«The very meaninglessness of life forces man to create his own meaning. If it can be written or thought, it can be filmed.» (Stanley Kubrick)

«The very meaninglessness of life forces man to create his own meaning. If it can be written or thought, it can be filmed.» (Stanley Kubrick)

The hotel I’m staying at faces a cemetery. It stretches out quite generously below palm and pine trees, surrounded by ancient-looking stone walls. Opposite its main entrance there is a tall and beautiful burial vault towering the yard, looming in like a memorial to all of those who move faster than death.

Entering the vault is like stepping through a gate, out of the blurring heat and an incessant stream of noises and daylight into the cool shade – a quiet vacuum which knows no time. The vault offers protection, it smells of moss and moldiness and the kind of comfort which is granted at the end of a lost battle. On the outside, the walls are warm, unruffled, and touching them reminds me of a line in Gabriel Mascaro`s «Ventos de Agosto»: «Rocks are breathing. They have lungs, just like any human being.»

It may seem odd at first, what Jeison (Geová Manoel Dos Santos) is trying to explain to a scientist there, who has come to record the winds, the air, the noises: an archeologist from the future, really.

Both are looking at a natural stone pool through which water is compressed along the movement of the tides, rising and falling, rising and falling: the rocks are breathing the sea.

Mascaro’s debut feature film is full of beautiful images and moments like this one, and their strength lies in the fact that he manages to capture them modestly, almost casually, giving his attentive observations of nature and surroundings all the space they need and just the space they can fill. Clearly, this director has a fine sense for the interplay of inner worlds and exterior conditions, and an empathy for different perspectives – displayed also in his latest documentary «Doméstica» about housemaids in modern day Brazil, also speaking about a country’s inability to deal with remembering and reliving a history of slavery.

For «Ventos de Agosto» Mascaro turned to an area along the coast of Pernambuco, northeast Brazil, around the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which produces the so-called August winds, famous for their distinct sound.

For «Ventos de Agosto» Mascaro turned to an area along the coast of Pernambuco, northeast Brazil, around the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which produces the so-called August winds, famous for their distinct sound.

Few people live in the small and apparently quite secluded settlement where Mascaro locates Jeison and his girlfriend Shirley (Dandara de Morais), who seem like the remote equivalent of a young and innocent Adam and Eve. They spend their days on a small boat, tanning and diving, or harvesting coconuts, secretly making love on a heap of green fruit whenever they are on their way to unload the truck later.

There is a photographer wandering about the place, trying to sell his portraits to people who don’t want to spend their sparse money on re-buying their memory from a stranger. And at one point, we see a tourist boat quietly passing by in the corner of a frame.

Shirley’s mother has assigned her to take care of her fragile grandmother and Jeison is the sole support for his ailing father.

Unlike Jeison, Shirley feels stuck and works on training her skills to become a tattoo artist. For a start, she leaves her creative imprint on the shaved behind of an annoyed pig.

One day though, things … stay the same, but Jeison changes. It’s a skull he finds when he’s diving, which causes a steadily advancing crack in the bubble of the almost-carefree naivety and protectedness him and Shirley had still been living in. Irritated by its sudden appearance out of nowhere, Shirley and Jason try to learn who the skull belonged to (their only indication being a gold tooth still stuck in the bone). Mascaro skillfully takes this chance for hilarious low-key dialogue and the introduction of a subtle discourse to develop from within the film now.

Like an all too cautious harbinger, the skull hardly prepared Jeison for the discovery of a dead body floating in the sea just a few days later. Pulling it out of the water, Jeison is facing mortality fully entering his life now and, at first, he cannot cope.

Like an all too cautious harbinger, the skull hardly prepared Jeison for the discovery of a dead body floating in the sea just a few days later. Pulling it out of the water, Jeison is facing mortality fully entering his life now and, at first, he cannot cope.

He lays out the body in front of his father’s house, covers it in blankets to suppress the pungent smell, washes it and shies away the flies and crows surrounding it soon. In the meantime, he’s recurrently trying to call the police, and for this he has to climb an overgrown hill, where he almost disappears within the high grass and the green. He wants police to come from the city to pick up the dead body, to identify it, give it a name, a history of a life that ended – or at least a grave, please. A space, a trace, a place in time, some meaning. But nobody comes.

Always subtly playful and with an undercurrent sense of humor and excellent use of diegetic sound, Mascaro – who was his own DP here – frames his characters in spacious shots where they are allowed to move. At the same time, he fully encompasses the powerful magnitude of nature and the inevitable course of time, revealing how subject living beings are to those forces, without ever betraying their dignity.

Jeison, in contrast to Shirley, only gradually recognizes a sense of protesting within himself. He has been content living along the rhythm of nature surrounding him, breathing like a rock, steady and not scrutinizing things. It’s only now that he comes to realize he will not remain. Not there nor anywhere, not on this earth forever. He is in the process of fully comprehending life’s limits, but he cannot accept its transitory quality yet. It scares him that the sea will claim everything at some point and in an attempt to prevent that, he sets up a stone well on the village’s graveyard, which is located at the beach. Of course, the coffins will be swept out of their sandy graves sooner or later, but there I take a look at the steadfast vault once more, and then I leave.